About the exhibition

Opening days 5 – 7 September 2025

Exhibition 9 September – 11 Oktober 2025

https://curatedby.at

At a time when we are overwhelmed by constant distraction and media irritation on the one hand and forced self-presentation on the other, Simon Schubert uses his analytical sculptures and immersive works on paper to pose the question of the location of the self. Where do I stand and how can I succeed in asserting myself? With the changeability that is demanded of us today, our own identity can sometimes slip away – as happens to Alice, who, in the all-confusing land of wonders, can only answer the question of who she is by admitting: “I hardly know, at the moment”.

In his Self-portrait (Selbstportrait) from 2014, on the other hand, Simon Schubert concentrates on the undeniable facts. He fills all the individual substances that his body contains in the appropriate quantities, neatly separated into gas bottles, jars and vials: a kit of life, arranged in a glass display case. The display is reminiscent of a scientific laboratory, but also of Snow White’s coffin. Could life, a soul, be breathed back into this person who has been broken down into its biochemical components?

Schubert’s upright Dewar body (Dewarkörper, 2024), like the display case, roughly corresponds to the dimensions of his body. He used Dewar vessels (named after their British inventor), which are difficult to identify at first glance and which we find in commercially available thermos flasks. The exposed, mirrored interior of the jugs indirectly refers to people’s inner lives. Schubert refers here to Leibniz, for whom, according to the theory of monads, each self-contained monad (soul) expresses the whole world from its perspective like a living mirror. However, he translates this idea into our age of fragmented subjectivity: the sculptural counterpart is composed of a multitude of insulating vessels. The multiplication of the conceivable – material or immaterial – contents stored inside corresponds on the surface to a diversely refracted mirror image in which viewers find themselves multiplied.

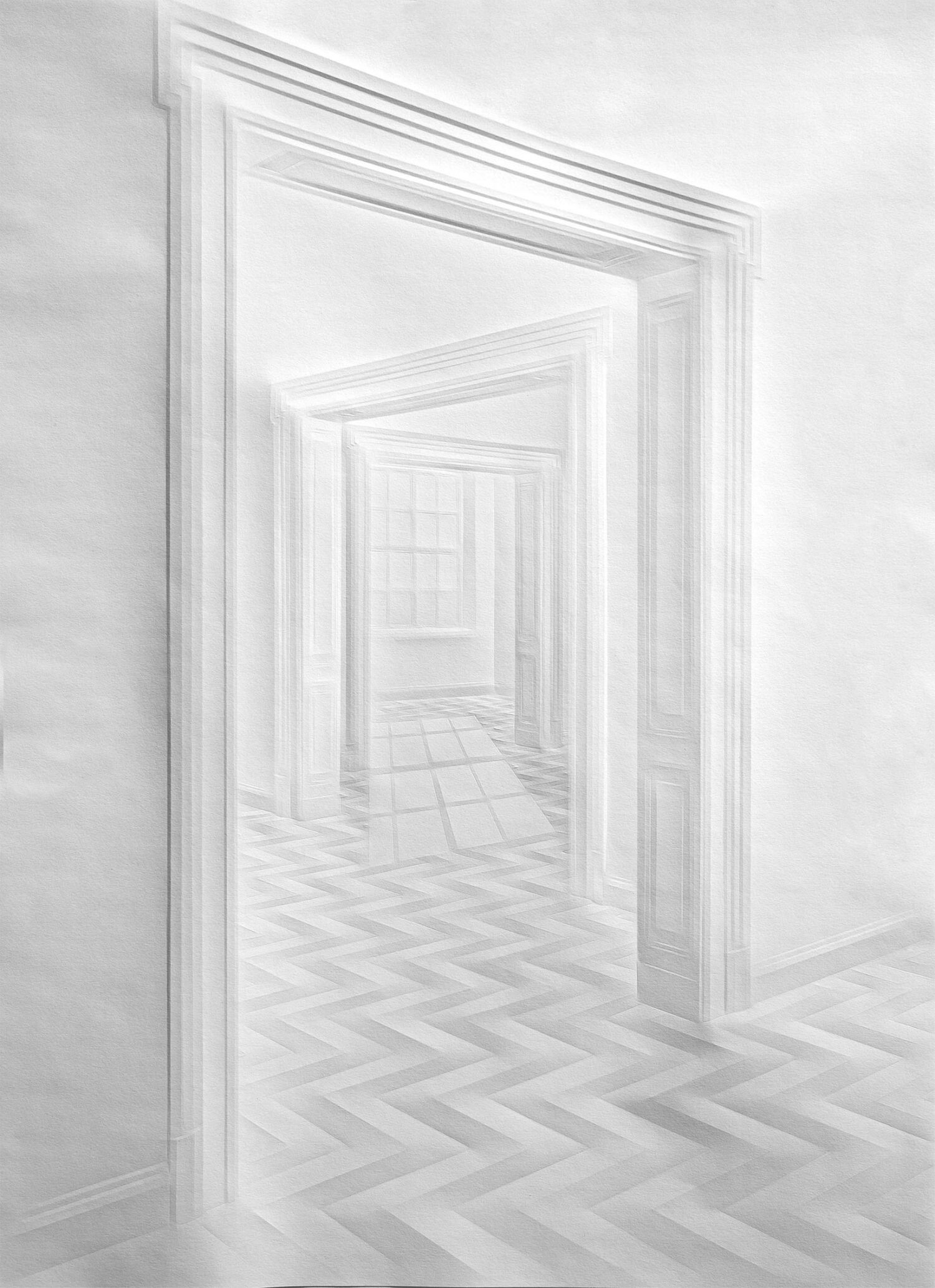

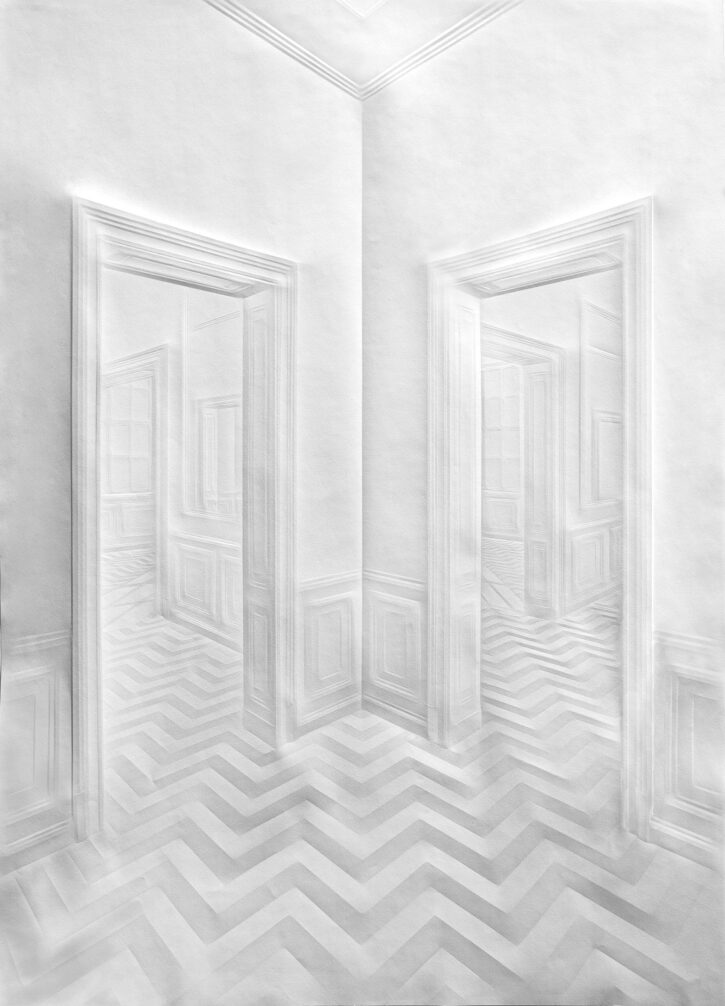

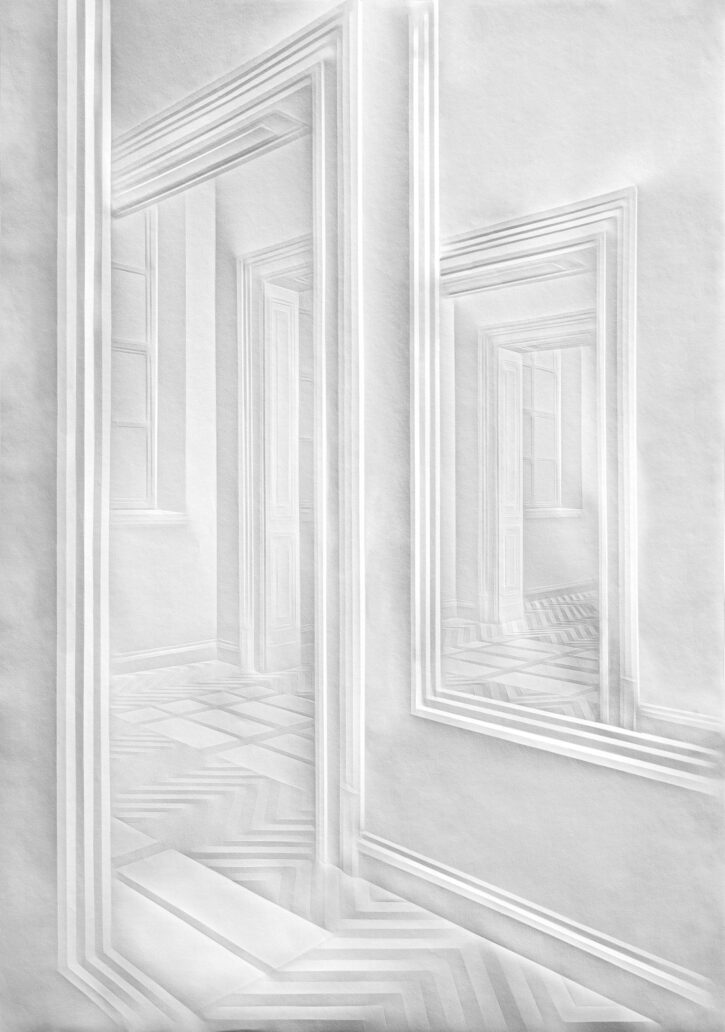

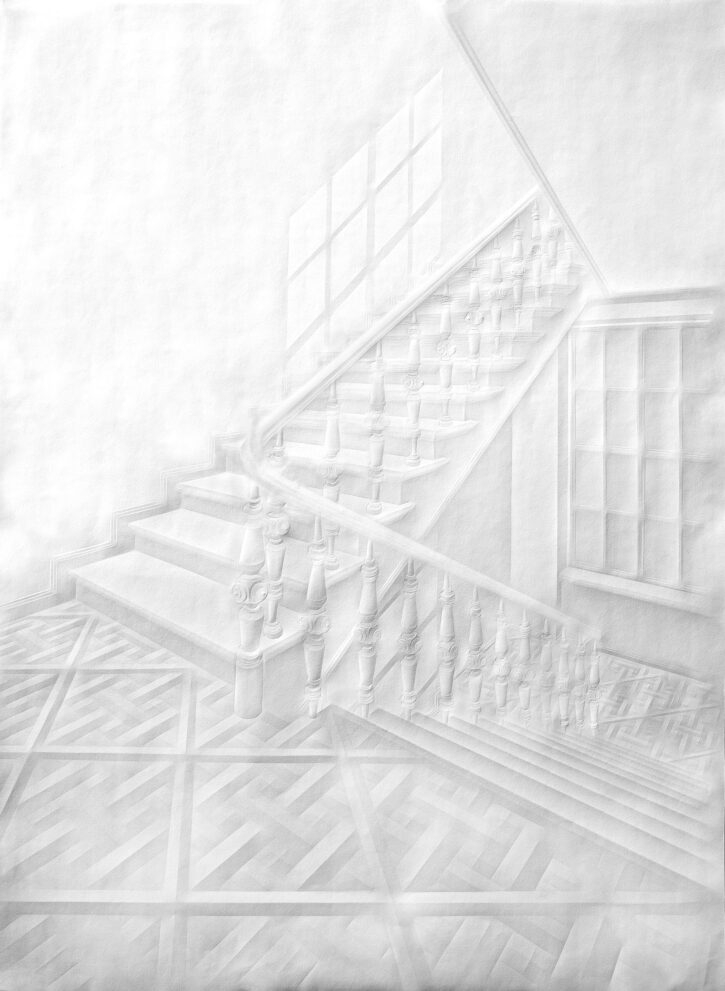

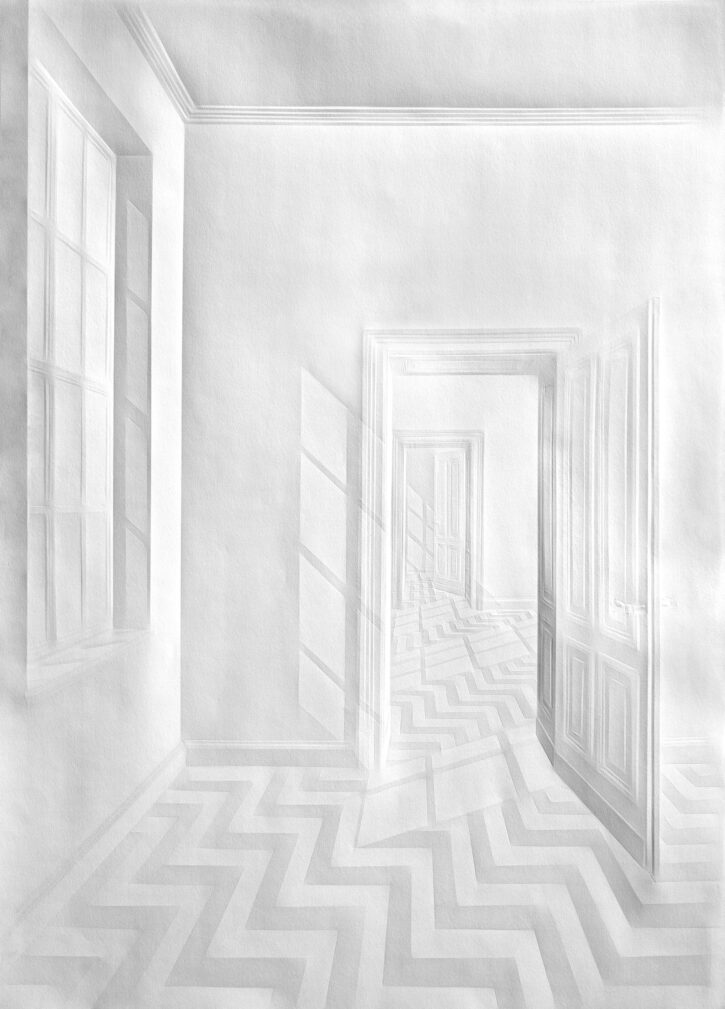

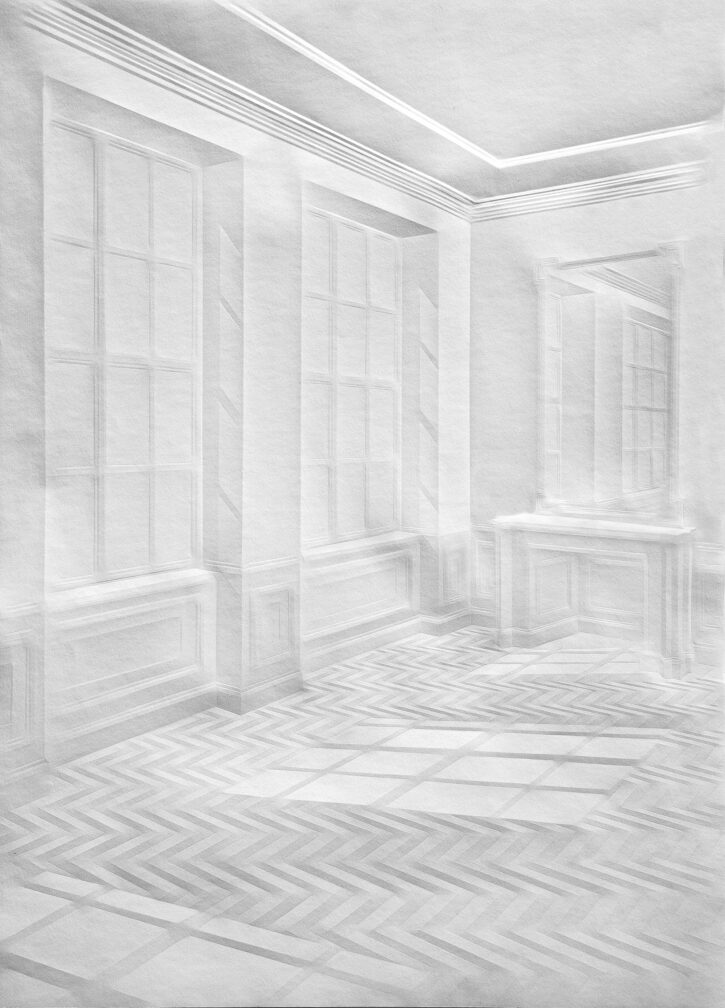

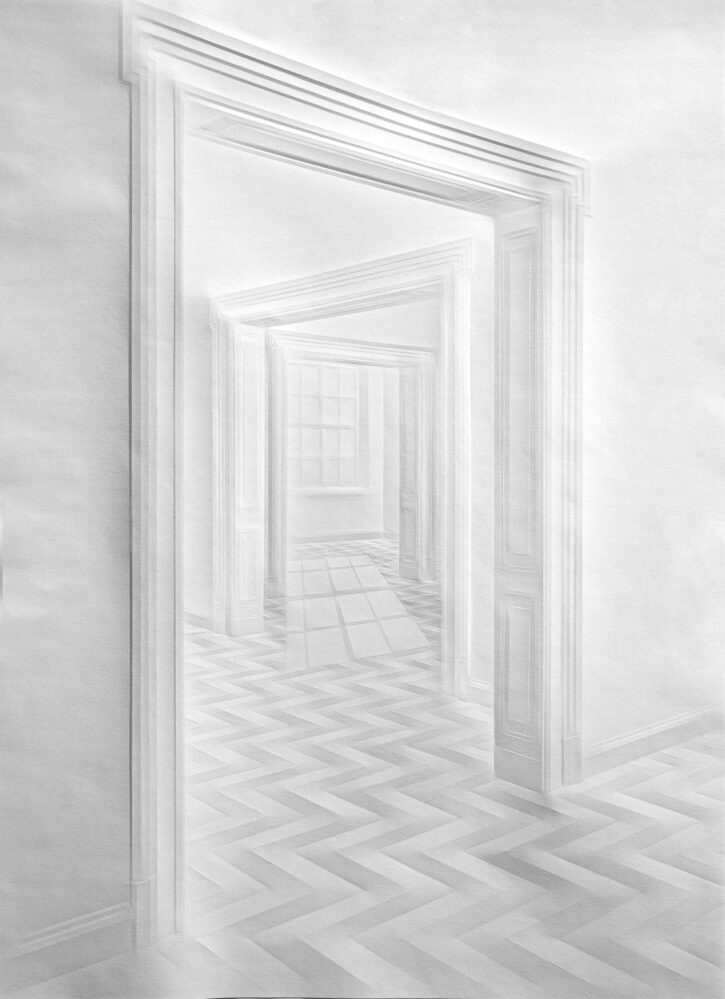

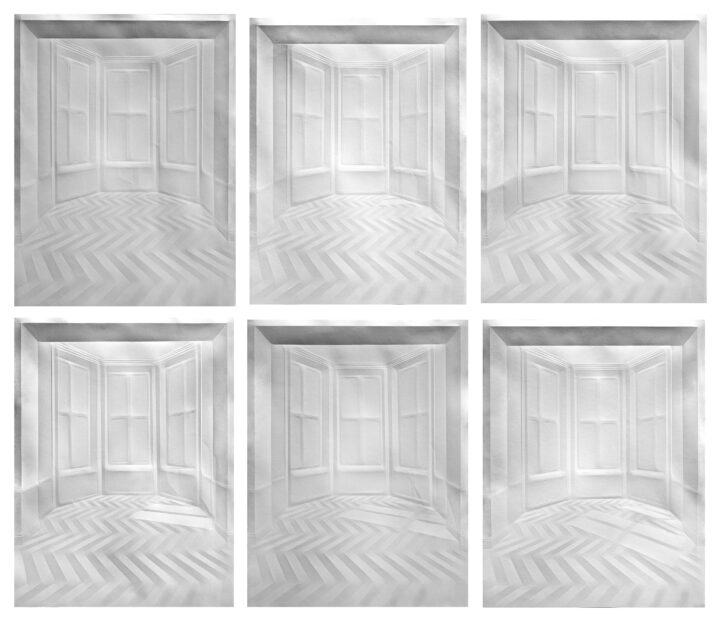

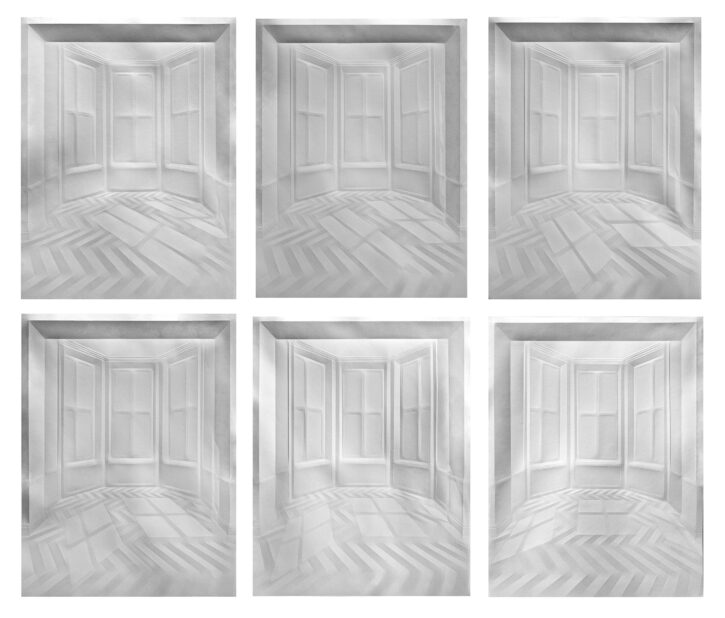

The two sculptures are surrounded by the virtuously folded paper works with which Schubert has become known. He works the paper like a sculptor, adding precise creases and creating relief-like drawings that – once they have been placed in the right light – translate the flat sheet into three-dimensionality and open up imaginary interiors. The viewer is drawn into long corridors and winding staircases, doors and vistas open up into ever new interiors.

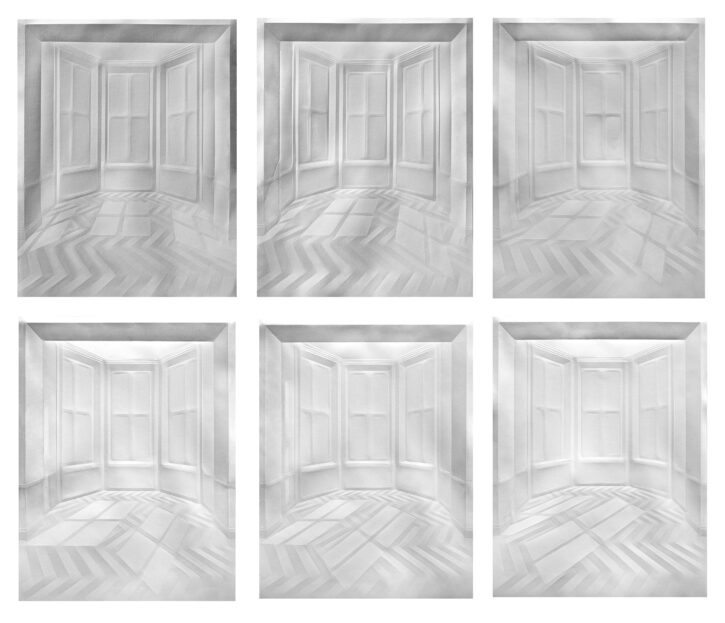

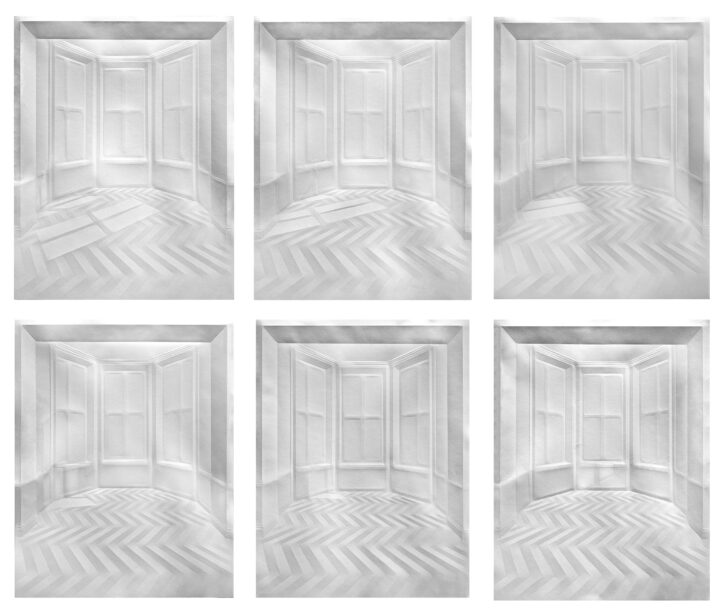

A series of 24 small-format paper folds titled Bay Window Light (Erkerlicht, 2025) illustrates how the incoming light, which changes over the course of the day, makes rooms appear, models and changes them. The simulation is deceptively real, and yet we cannot enter the place. Nor do we know for sure whether we are seeing a window, a view through or a mirror or a picture within a picture at certain points in Schubert’s folds.

Schubert intensifies this experience of uncertainty, the play with perception, in his paper installations. Especially for this exhibition, a new, walk-in space made entirely of paper has been created by partitioning off a room. We are invited to immerse ourselves in a parallel world, with white walls made of folded paper, a double floor and optically expanded spaces that extend beyond the real spatial boundaries. On entering the installation, we become part of a real staging and at the same time part of the illusion that unfolds here: The illusion of space within space within space.

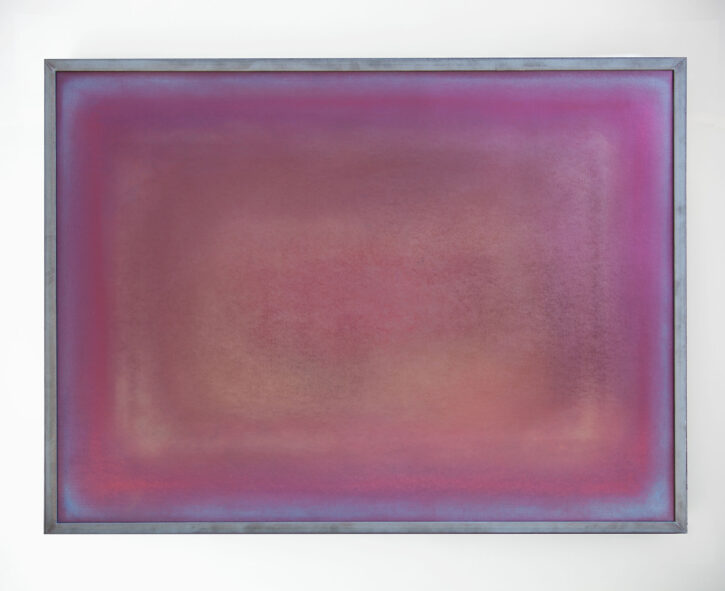

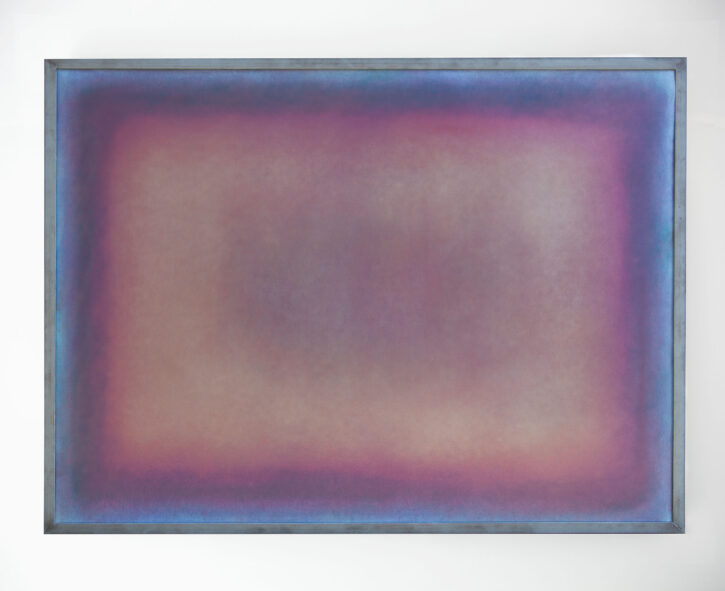

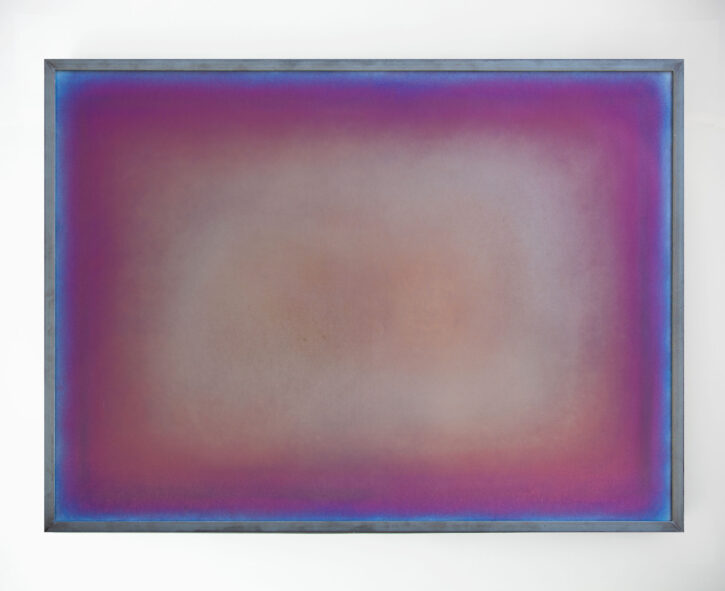

In addition, a kind of counter-space, a vague, gloomy realm of shadows, seems to open up in one of Schubert’s Spatial Mirrors(Raumspiegel, 2025) on each of the four walls, which is strikingly different from the light, linearly constructed architectural folds. Heavy metal frames enclose spaces that are lost in mists of color and are reminiscent of the opaque surfaces of historical mirrors. Schubert uses pigments here that change color when rubbed into the paper surface – an almost alchemical process in which he charges the pictures with energy and atmosphere.

What Simon Schubert’s interiors have in common is that they are not places of self-assurance, but places of questioning. Like Samuel Beckett’s plays, which strongly influenced him in his early years, his paper spaces lead us back to ourselves and into the labyrinths of our inner world. If we enter his fragile folding spaces, which – when the light fades – can dissolve back into the white of the paper at any time, then the surreal danger of our own disappearance also resonates.

Schubert intensifies the implicit reminder of one’s own transience with a vanitas sculpture placed in the middle of the paper space: his Time Capsule (Zeitkapsel, 2025) consists of crystals of the heavy metal bismuth that he has grown himself and then soldered together. Although bismuth is not hazardous to health, it is very slightly radioactive and extremely stable. It has a half-life of no less than 19 trillion years: an immeasurable period of time for us humans and hardly comprehensible even by cosmic standards, after which this time capsule will release its unknown interior – a period of time that makes us reflect, perhaps also admonishing us to be modest and mindful.

Like the interiors of the final scenes of Stanley Kubrick’s Odyssey in Space, which oscillate masterfully between time and space, Simon Schubert’s works seem to be freed from certain constraints of space and time. They point the way into a constantly growing edifice that the artist has been working on for some time and which, taken as a whole, can also be seen as a complex self-portrait: The artist sees each of his paintings, each paper folding, each graphite drawing and pigment work as a view into this proliferating building, each sculptural object as an object of furnishing. The room installation he has set up in the gallery becomes a walk-in part of this building for the duration of the exhibition and opens up a multifaceted space for reflection.

Schubert’s works combine a strong physical presence that invites us to concentrate and pause, with a philosophical depth that prompts us to speculate on the question of who we are and in how many parts (subjects). And whether there is such a thing as a core, an essence that we can preserve and fall back on when we are in danger of losing ourselves again.

Fritz Emslander

Simon Schubert (*1976) lives and works in Cologne.

Fritz Emslander (*1967) is acting director of Museum Morsbroich, Leverkusen.

Further informations: